All you wanted to know about Rightwing

Ravi Shanker Kapoor | November 20, 2016 2:48 pm

With victory of Donald Trump as President in the US, the rise of the Right is being discussed with great interest and greater trepidation. The Right, if we are to believe the generally anti-Right mainstream media, comprises inconsequential weirdoes at best and dangerous loonies at worst. Therefore, it is time to understand what Rightwing means in the first place.

Well, everybody knows what the Left is; and it is pretty much the same all over the world. The Indian Leftist is little different from his American, French, German, and British counterparts: all of them stand for, and against, similar ideas and ideals. For greater state control over the economy, trade unions, women’s rights, welfare state, protection of minorities, affirmative action, some variant of multiculturalism, etc.; and against business monopolies, the corporate sector, tradition, death penalty, etc.

But what, pray, does the Right stand for all over the world? Certainly not capitalism, though it might seem to be an obvious answer to many. Our very own RSS is against capitalism, so also are certain strands of the American Right. Nationalism? While the RSS is all for it, libertarians scoff at the very idea of nationalism. Religions, culture, and tradition? Hindutva and Burkean conservatives in the UK and the US cherish it, but the followers of Ayn Rand are fiercely opposed to it. Freedom of expression? All manner of Western Rightists support free speech, but the saffronites curtail it severely. So, what is the common thread, if there is any, running through the myriad Rightwing ideologies? Or is the term ‘Right’ just nominal in nature—referring to anything opposed to the Left but signifying nothing substantive?

Let’s begin with the beginning. The terminology owes its existence to the seating arrangements during and in the aftermath of the French Revolution (1789–99). While the votaries of the established, monarchical order, ancien régime, sat to the right of the chair of the parliamentary president, those who wanted change sat on the left. In other words, those sitting on the right were monarchists, feudal lords, clerics, and traditionalists, whereas on the left were the champions of liberty, modernists, secularists, and representatives of modern classes.

Over the decades, or rather centuries, the ideologies emanating from the beliefs and interests of two wide-spectrum assortments have been called Leftwing and Rightwing. The categorization has never been crystal clear; usually, it is nebulous and confusing; sometimes, it is downright wrong. For instance, reputed publications like the New York Times refer Pakistan’s jihadist outfits Jamaat-e-Islami and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam as “right-wing religious groups.” I shall prove that this is an erroneous and misleading description.

When the ideological battle-lines were drawn at the fag-end of the 18th century, the man who appeared to have emerged as the champion of ancien régime was Edmund Burke (1729-97)—the father of conservatism. Encyclopedia Britannica has simply but beautifully described conservatism as a “political doctrine that emphasizes the value of traditional institutions and practices.” Conservatism, which was the earliest Rightwing ideology, “is a preference for the historically inherited rather than the abstract and ideal. This preference has traditionally rested on an organic conception of society—that is, on the belief that society is not merely a loose collection of individuals but a living organism comprising closely connected, interdependent members. Conservatives thus favor institutions and practices that have evolved gradually and are manifestations of continuity and stability. Government’s responsibility is to be the servant, not the master, of existing ways of life, and politicians must therefore resist the temptation to transform society and politics.”

Since institutions, practices, traditions, and conventions have evolved gradually, they cannot and should not be changed without proper reflection and prerequisite preparation, not in obsession with novel, however tempting, ideas and certainly not arbitrarily. For, as Burke wrote, “Society is indeed a contract… [It is] a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.”

Conservatism is also not very comfortable with the Renaissance and Enlightenment idea of human perfectibility. Conservatives were religious people, and the Christian concepts of original sin and human fallibility were at odds with infinite corrigibility. As Burke said, “A spirit of innovation is generally the result of a selfish temper and confined views. People will not look forward to posterity, who never look backward to their ancestors.”

Though suspicious and skeptical of change, conservatism is not opposed to it. So, Burke said, “A State without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation.” Again: “You can never plan the future by the past.” And: “The arrogance of age must submit to be taught by youth.” Absolute fear of and stiff opposition to change is reaction, not conservatism. Reactionaries react violently to change; conservatives conserve what is worth conserving while cautiously welcoming change.

With such a line of thinking, Burke’s discomfort with and opposition to the French Revolution is not surprising. The Revolution was an abrupt breach with the past in every conceivable manner; this angered and anguished the father of conservatism. He wrote in the Reflections on the Revolution in France, “I should therefore suspend my congratulations on the new liberty of France, until I was informed how it had been combined with government; with public force; with the discipline and obedience of armies; with the collection of an effective and well-distributed revenue; with morality and religion; with the solidity of property; with peace and order; with civil and social manners. All these (in their way) are good things too; and, without them, liberty is not a benefit whilst it lasts, and is not likely to continue long.”

His words proved to be prophetic, as Revolution in France soon started devouring its own children; there was a reign of terror, mass slaughter (including that of a large number of innocent people), wars, destruction and devastation in entire Europe.

Burke’s reflections did not go uncontested, the most prominent criticism of which came from Thomas Paine (1737–1809), an English-American philosopher, political theorist, and revolutionary. In Rights of Man, he inveighed against Burke’s social contract as a partnership “between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” According to Paine, “Every age and generation must be as free to act for itself in all cases as the age and generations which preceded it. The vanity and presumption of governing beyond the grave is the most ridiculous and insolent of all tyrannies. Man has no property in man; neither has any generation a property in the generations which are to follow… Every generation is, and must be, competent to all the purposes which its occasions require. It is the living, and not the dead, that are to be accommodated. When man ceases to be, his power and his wants cease with him; and having no longer any participation in the concerns of this world, he has no longer any authority in directing who shall be its governors, or how its government shall be organized, or how administered.”

Many authors find the ancestry of conservatism-Rightism and liberalism-Leftism in Burke and Paine, respectively.

In today’s world, the ideological-political divisions don’t appear to be so sharp or well-defined. As I mentioned earlier, in our country the RSS, the Political Right which values tradition, is Left-leaning as far as economic policy is concerned; and, concomitantly, liberalizers representing the Economic Right are Left-leaning when it comes to political (Kashmir, jihad), social (LGBT, how women should dress), and cultural (freedom of expression) issues.

Yet, on one point, there is some kind of agreement: the role and importance of tradition which no Rightwing thinker would like to eliminate, minimize, or traduce. This may sound grossly erroneous in the face of libertarians’ dislike for tradition. Ayn Rand, for instance, wrote, “The plea to preserve ‘tradition’ as such, can appeal only to those who have given up or to those who never intended to achieve anything in life. It is a plea that appeals to the worst elements in men and rejects the best: it appeals to fear, sloth, cowardice, conformity, self-doubt—and rejects creativeness, originality, courage, independence, self-reliance. It is an outrageous plea to address to human beings anywhere, but particularly outrageous here, in America, the country based on the principle that man must stand on his own feet, live by his own judgment, and move constantly forward as a productive, creative innovator.”

My point, however, is that the tradition libertarians implicitly stick to is the (classical) liberal one; this tradition predates Burke, and it has gleaned elements from Hellenistic as well as Christian doctrines. In a way, all true liberals, in contradistinction with the Trump-hating grandees, are conservative.

This brings us to the issue of referring Islamists of Pakistan and elsewhere as ‘conservative.’ This is absolutely wrong, because they have supplanted local cultures with the contrivances sanctioned by Islam which is Arab imperialism. Pakistan is the extreme example of Islamism-inspired deracination: it is the only nation that has been made to import two most important elements of mankind—language and religion. The cultures and traditions of other Muslim nations have also suffered at the hands of religious conservatives in varying degrees. It is only the Arab nations and principalities that can be conceivably called conservative.

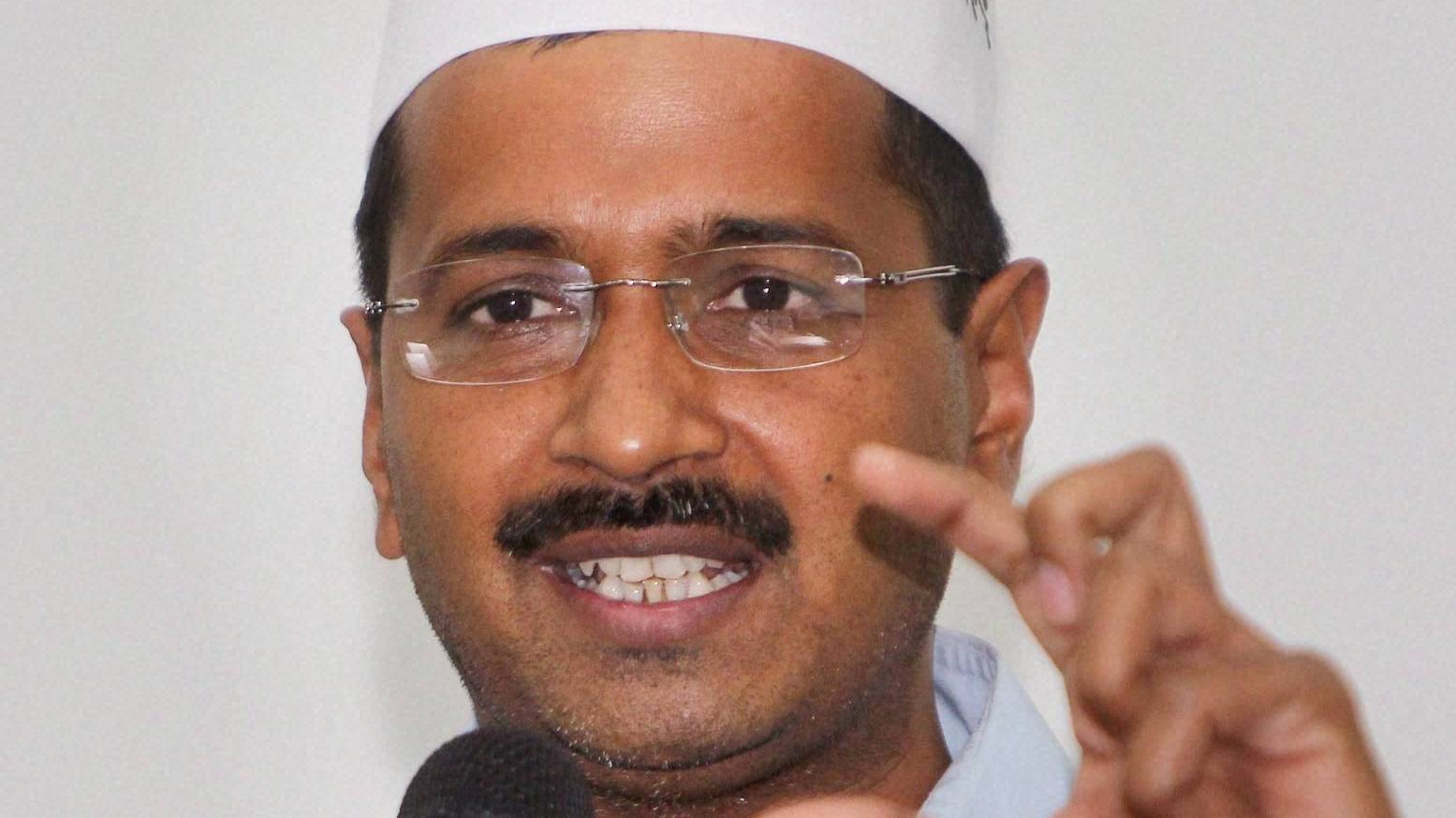

In a nutshell, Rightwing is about tradition. It is another matter than the received wisdom is that Rightists are an assortment of crazies. So, Donald Trump is a racist, Islamophobe, xenophobe, etc.; Narendra Modi is a mass murderer; Sarah Palin is semi-educated; Subramanian Swamy is mad; and long goes the list of Rightwing loonies. Public intellectuals need to realize that there is more to the Right than their outlandish theories and outrageous views.